The state Lands commissioner race here in Washington State, USA, is in full swing and I find myself contemplating complexity, in particularly that of the natural world. I’ve been thinking about complexity ever since the Embracing Nature’s Complexity conference, where I came to see complexity not as something merely complicated, but as a sublime and fundamental substrate of all life. And so it is with legacy forests. Their complexity is their essence. And yet, in the heat and rush of politics, the deep and nuanced, multifaceted story of these forests is mostly lost amidst the reductive, simplistic narratives of industry.

It’s a shame, because it’s in complexity that we encounter things as they are. Life is a complex of relationships, and only when we see those relationships do we see our own entanglement within them. It’s also where we discern the patterns that are critical to the decisions we make about how we interact with and “manage” the land.

Like all good complexities, legacy forests have a context—the primeval forests that were here originally. So let’s begin there.

Before there was a Washington state, the lowland forests (below 3,500 feet) existed for eons in relationship with a diverse tapestry of tribes, such as the Nooksack, Lummi, Snoqualmie, Elwha, Quinault, Chehalis, Cowlitz and numerous others. I say “in relationship with” because that’s how these tribes refer to the lands and beings around them, as relations. It’s not like they didn’t use the forests, they used them in all sorts of ways. They cut trees for canoes, longhouses and totem poles, stripped cedar bark for baskets, and set burns to favor certain plants and animals, all carried out in a manner in which the forests clearly thrived. One of the first European arrivals, Captain James Cook, described the land as “luxuriant” from shore to mountain peak. Settlers arrived to encounter forest Valhallas, with canopies vaulting 300 feet in the air, held up by 800-year-old cedars, firs and spruce, bulging wide as a horse is long, nurturing streams choked with salmon twice as large as those of today.

As far as forest health is concerned, this would be our baseline, our optimum condition—the forests that existed prior to Western settlement. Not only did those forests nurture a stunning richness of life, they nurtured the water cycle and climate, churning vast amounts of water vapor and rain-catalyzing particles into the atmosphere, feeding upland rains, which of course came back as rivers and creeks, which the great forests transpired again into the atmosphere—a healthy, functioning inland water cycle.

Unfortunately, those forests are mostly gone now. Since around 1850, virtually all of Washington’s lowland forests have been logged. But as I said, it’s complex. Not all logging was the same. There was preindustrial and post industrial logging, and they were very different practices, leaving behind very different landscapes.

Prior to 1940, forests were cut by hand, and more selectively, with smaller trees left behind, as well as hard to reach ones in ravines and on steep slopes. And then they were abandoned, which was actually a good thing, because it allowed the forests to recover according to their own natural processes and genetics, and therefore carry forth the legacy of what was there before. Thus the name, Legacy Forest. When we talk about legacy forests, we are generally talking about what remains of these pre-industrially cut forests, a little younger than old-growth, but on their way.

After 1940, logging entered a new era, the era of “scientific management.” Subsequently, (though practices have evolved) forests were completely clearcut, with very little forest beyond reach of the new industrial machinery. The new goal wasn’t simply harvest, but complete conversion to timber production, spraying back the forests’ attempts at recovery with herbicides, then replacing it with something considered more productive, like planted monocrops of Douglas Fir. The practice continues with minor modifications, essentially converting the land from the primeval forest’s successful attempt at recovery to a human-designed plantation, a crop.

Though still called a forest, someone passing between one to another would not only see but feel the difference, as I described a couple years ago after joining a group of people visiting a legacy forest named Bessie. The first paragraph describes hiking up a logging road with managed plantations side to side.

Trees pass on either side, but that is all. Just uniformly sized trees crowded with other trees, branches jutting into branches, little light or life between them, the sky dim, choked off.

Then, at the end of a spur, after plunging into the trees and traversing the side of a hill, there is sudden spaciousness and light, with fewer trees but each one individual. Some rise from yard-wide trunks, others are slender and lacy, like the hemlocks filling the understory. Snags and fall-down blaze with a wild profusion of mosses and algae. You are standing in Bessie.

Very quickly you see why such places are critical for wildlife. Everywhere is the evidence: mossy snags drilled out by woodpeckers, larger cavities where nests are hidden. On the mossy carpet elk droppings are followed by bright, freshly pecked chips of wood. The scientific term, biodiversity, reveals its meaning.

You also see why such forests are carbon drawdown powerhouses. Carbon sequestration is roughly the turning of atmospheric CO2 into plant life and soil. By the might of their trees and richness of life, mature, lowland conifer forests like Bessie can do this as no other ecosystem on earth.

It’s ironic we speak of Bessie as an “older forest.” Whether 115 or 150 years old, its trees are meant to live to 800. Bessie is actually just getting started.

If you visit, go in August, for then you’ll discover Bessie’s other superpower, the ability to hold water and keep cool. All those mosses, rotting trees and thickly piled soils act like sponges, absorbing bountiful winter rain and holding it, banking it against the dry summer months and possible drought to come. DNR’s plantations, too biologically poor, can’t do this as well. In their midst, Bessie is a critical island of hydration and cooling.

Now you see the essential matter. It is one of conversion, of converting the land’s original biotic legacy to a man-made agricultural system. Once that legacy is cut, sprayed and replanted, it’s largely gone, (though given time, it can self-heal and gain the structural and biotic diversity of a real forest.) In effect, it’s like turning a natural tall grass prairie into a cornfield. They are two different entities, and yet as you’ve probably noticed, it took a little explaining to show that. There’s context and complexity to convey, all of which is almost impossible to explain in stump speeches (forgive the pun) candidate debates or letters to the editor.

As a result, the industry’s choice in this race, Jaime Herrera-Beutler, has been able to make broad claims without any real inspection. What are those claims? Again, a little context is needed; it involves wildfire, and few things are as complex as wildfire. For one, wildfire is natural, so there is also the question of whether the fire is supposed to be there or not. This is hard to answer because the forests themselves are no longer natural. Our baseline of primeval forest is gone, and in it’s place sprawl plantation forests which are prone to both disease and fire. There is also the difference between low intensity fires and high intensity fires, both of which play different roles in ecosystems upon which numerous species depend. Complicating the matter even further is global warming, raising atmospheric temperatures and drawing more moisture out of the land. And if that isn’t complex enough, remember that our current climate conversation doesn’t yet include the water-cycle effects of land disturbance, such as forest conversion. Though I, and many others, are working on that.

It is into this cauldron of complexity that Jaime Hererra-Beutler makes her broad claims. The forests are undermanaged and “falling into disrepair,” she says, and need “cleaning up” lest they become “tinder boxes.” She wants to “restore them to health,” and that means “more intensive management.”

But what she doesn’t specify is which types of forest she is talking about. Does she mean legacy forest or converted forest? If she means converted, managed plantations, or what is often called “working forest,” her points about overcrowding make some sense. Oftentimes, plantations are replanted too densely and could benefit from thinning. In fact, some legacy forest defenders are working on finding ways to create more forest jobs through artful, labor-intensive thinning for habitat creation (Though forests can accomplish this themselves for much less money through the natural processes of disease and fire.) But clearly she doesn’t mean working forests. Forest defenders aren’t even opposing logging on already converted forests. What she means is legacy forest, and there her arguments are both counterintuitive and scientifically flawed.

Conditions that favor fire include heat, dryness and wind velocity, all of which are exacerbated by thinning. Legacy forests, on the other hand, are naturally cooler, moister and calmer than their managed counterparts. It is easy to see why. Mosses, downed logs and rich forest duff act as sponges, holding moisture from the wet season into the dry. The complex multistory canopy keeps wind at bay and captures moisture from fog. The layers of trees cool the air through evapotranspiration. It’s why scientific studies show lower fire intensity in mature, complex forests as opposed to plantation. It’s also why wildlife seek these forests out during fires as refugia.

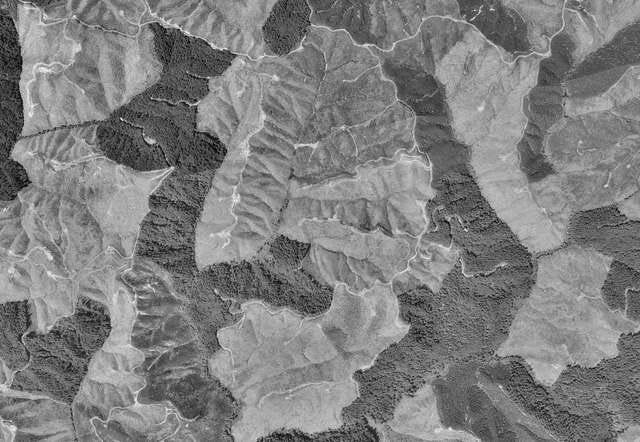

By the way, here is a picture of what forest “undermanagement” in Washington state looks like. All those tan divots are clear cuts.

And a closer view:

Not all that land is state forest. Most of it is private, but the pattern is pretty uniform. Notice the difference in shades. The lighter green is new regrowth, the darker green older forest. Amongst that darker green may be seams and patches of Legacy Forest. And apparently, according to Hererra-Beutler, those fragments are causing the forests to burn and therefore need to be logged.

Is there any reality to that argument? It doesn’t look like it. Yet it’s repeated again and again without correction because, well, what politician is going to try and explain it all? Though, if they did try, they just must find that there’s not a devil in the details, but a mighty powerful angel.

Notice also the bright ribbon in the lower left corner. That’s a creek. Such creeks are critical for the area’s salmon, which need cool, clear water to spawn. They in turn are critical for the Southern Resident Orca in the waters to the west, which need big, fat salmon to survive. All are are sliding towards extinction. Another reminder of how everything is connected.

But such interconnection and complexity is not easy to get across in a political campaign. Hererra-Beutler has clearly gotten better traction with her simplistic reduction. “Too many of our forests have been undermanaged or outright neglected, and they’ve turned into crowded, diseased tinderboxes, just waiting for a spark,” she says.

Yesterday morning, Washington state’s largest newspaper, the Seattle Times, endorsed her for Washington’s Commissioner of Public Lands, citing her aggressive views on wildfire.

Sources:

Bradley et al. 2016. Ecological Society of America. Does increased forest protection correspond to higher fire severity in frequent-fire forests in the United States? https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1492

Hanson, Chad, T. 2021. Birds. Is “Fuel Reduction” justified as fire management in spotted owl habitat?. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds2040029

Countryman, C.M. 1956. Fire Control News. Old-growth conversion also converts fire climate. (From the abstract: Discusses the alteration caused by partial cutting in air temperature, relative humidity, wind velocity etc. within the stand, which may greatly increase fire hazard irrespective of the amount and kind of fuel.)

Levine, et al. 2022. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. Higher incidence of high-severity fire in and near industrially managed forests. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2499

DellaSala, et al. 2022. Biological Conservation. Have western USA fire suppression and megafire active management approaches become a contemporary Sysyphus?

Thanks for reading! I’m glad you’re here. I keep this page free for all and avoid littering the text with subscriber requests. But that doesn’t mean I don’t completely depend on reader-generosity to make this work possible. Please become a paid subscriber if you can.

In some way, I find that it is not the clear cut that is the worst, but the planting following it. Of course, I speak about forests that have already been managed and not old growth. If you clear cut without planting, the result can be quite appealing and diverse, at least in my part of the world, Sweden. Planting is the step that really convert the land to agriculture style plantations.

Another great post